Almost every serious history

enthusiast in this country comes across the subject of Eastern Ganga (pronounced as Gangaw in Odia) Dynasty and yet strangely; the subject is, overlooked repeatedly across our national

history. The general approach on this particular historical juncture ends in

brief literature of concoctions and conflicting statements across loads of

academic documents. It is not within my capacity to put down every achievement

of this dynasty into one article. However, the magnificence in narrative of the dynasty’s struggle to power and ceaseless existence in the eastern coastal

frontiers of the Indian Subcontinent for nearly a millennium according to

proven archeology cannot, be ignored. Discussing some of its coherent military

achievements might open a brainstorming window for some of us into the other

aspects of this critical part of Odisha’s history.

Historically the Eastern Gangas existed in Odisha and parts of Northern Andhra Pradesh as a ruling family since the late third or late fourth century. During the previous Somavanshi rule, most of the Ganga families were limited to Southern Odisha (undivided Ganjam and Koraput) and Northern Coastal Andhra Pradesh. It was not until the rule of ‘Anantavarman’ Vajrahasta V in the mid eleventh century that a Ganga family broke out of their limits as subordinates and started military expansion of their power in the region. There were five prominent dominions of the Kalinga Ganga family in those days ruling from five different administrative centers namely - Kalinganagara (Srikakulam), Svetaka Mandala (Ganjam), Giri Kalinga (Simhapur), Ambabadi Mandala (Gunupur, Rayagada) and Vartanni Mandala (Hinjilikatu, Ganjam). The heartland of the Gangas had three parts of Kalinga namely, Daksina Kalinga (Pithapura), Madhya Kalinga (Yellamanchili Kalinga or Visakhapatnam) and Uttara Kalinga (districts of Srikakulam, Ganjam, Gajapati and Rayagada).

Historically the Eastern Gangas existed in Odisha and parts of Northern Andhra Pradesh as a ruling family since the late third or late fourth century. During the previous Somavanshi rule, most of the Ganga families were limited to Southern Odisha (undivided Ganjam and Koraput) and Northern Coastal Andhra Pradesh. It was not until the rule of ‘Anantavarman’ Vajrahasta V in the mid eleventh century that a Ganga family broke out of their limits as subordinates and started military expansion of their power in the region. There were five prominent dominions of the Kalinga Ganga family in those days ruling from five different administrative centers namely - Kalinganagara (Srikakulam), Svetaka Mandala (Ganjam), Giri Kalinga (Simhapur), Ambabadi Mandala (Gunupur, Rayagada) and Vartanni Mandala (Hinjilikatu, Ganjam). The heartland of the Gangas had three parts of Kalinga namely, Daksina Kalinga (Pithapura), Madhya Kalinga (Yellamanchili Kalinga or Visakhapatnam) and Uttara Kalinga (districts of Srikakulam, Ganjam, Gajapati and Rayagada).

‘Anantavarman’ Vajrahasta V:

During the rule of Vajrahasta V from 1038-1070 A.D the Gangas started

playing a prominent role from the southern horizon of the already weakening

later Somavanshi kingdom. He introduced the Anka year of calculation system for

the regnal years of the kings and this continued as a standard norm for future

kings of ancient Odisha. One of his predecessors had tried to unite the Ganga

dominions in the Kalinga Dandapat area unsuccessfully. Vajrahasta V had not

only united the Ganga domain but also had defeated the Somavanshis in his

northern frontiers. He established firm diplomatic and military relations with

the Kalachuris (enemies of the Somavanshi) by marrying a princess from their

family. He was also married to a princess of Ceylonese royal descent. The

Vaidumvas clan of Kanchipuram were his maternal side of the family.

A Vaidumvas family member named as Aditya

Chotta served in his military who later helped him in uniting Kalinga. The

Korni copper plate grant of Chodaganga Deva mentions that Vajrahasta V made land

grants to 300 Brahmins, which implies him conducting a Rajasyuya Yajna on his

own right after the unification of the Kalinga tract. For the first time

Vajrahasta V accepts titles as Trikalingadhipati (lord of the three Kalingas)

and Sakalakalingadhipati (lord of complete Kalinga) in the Ganga family after

his one and half a dozen known ancestors had ruled with the same farfetched

ambition. Thus began the imperial era of the Eastern Gangas.

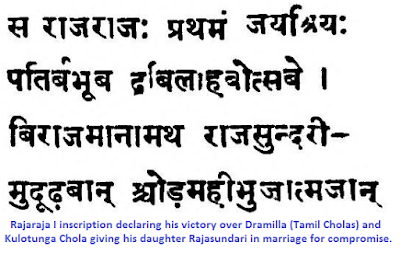

‘Devendravarman’ Rajaraja Deva I:

Rajaraja Deva I proved his efficiency

in expanding his father Vajrahasta V’s ambition over the united Ganga

dominions. He ascended the throne in

1070 A.D, the same as the year of ascension of the Chola Kulottunga I (later

crowned as Chola emperor). One of his Ganga Prasasti inscriptions clearly says

that he fought the Chola king over the territories of Vengi in the south, which

means he invaded the opponent to be certain. After the defeat of the Cholas,

Kulottunga I gave his daughter (sister?) Rajasundari in marriage to Rajaraja I.

Despite ruling for only eight years,

Rajaraja I was able to defeat the Somavanshi ruler ‘Mahasivagupta’ Janmenjaya II at the time when that dynasty was at its pinnacle of achievements

taking into consideration the completion of architectural marvels like the

Lingaraja Temple a few years before. The Southern portion of the Somavanshi

territory becomes a Ganga domain. The Dirghasi temple inscription of Rajaraja I

mentions his Brahmin commander in chief called Vanapati had assisted him in defeating

all the enemies on multiple fronts like the Chola, Utkala (Somavanshis),

Gidrisingi, Khemidi, Dakshina Koshala (Kalachuris) and Vengi (Eastern

Chalukyas).

‘Gangeswara’ ‘Anantavarman’ Chodaganga Deva:

Chodaganga Deva is the most debated

character among historians as he has left behind numerous inscriptions in his ancient empire. Seemingly, he lost, his father

Rajaraja Deva I at the age of five while his younger brother Parmardi was only

three years. He was heir to the expanding Ganga dominion, which was directly in

conflict with the Cholas and Somavanshis.

The territory of Vengi becomes a part of fierce contest for the

Gangas though ruled by the Cholas directly after defeating the Eastern

Chalukiyas. Kulotunga I had sent three out if his four sons as the governors of

Vengi after the defeat from Rajaraja I and marital agreement over his daughter

(?) Rajasundari (Chodaganga’s mother) with him. During the second governor

Virachoda from 1078-1084 A.D and while Chodaganga was a teenager, two Chola

officers were in appointment of Kalinganagara as Puravari and Lenka as per

inscriptions of Lingaraja and Mukhalingam temples indicating both the ruling

families had good relations. However, during the rule of the third governor

Vikramchoda Chola, hostilities began again.

The Tamil classic Kalingattuparani

says that due to non-payment of tributes (in defiance to Chola authority)

Kulotunga sent the Chola army under a Pallava named Karunakara Tondaiman, who

laid waste to the Ganga kingdom and returned to his master collecting lots of

wealth. Inscriptional records provide more details about these events. A

historical estimation says that Chodaganga was married to Chodadevi, a Chola

princess as per Daksarama inscription. Virachoda the former governor of Vengi

had married off his daughter to him and settled in Kalinga acting as a guardian

to him. Loosing large parts of his kingdom to the Chola forces due to his

inexperience in war, Chodaganga is, invited by the Somavanshi Brahmin minister

and general, Vasudeva Ratha to oust the incompetent Somavanshi king. According

to folklores, Chodaganga Deva reached at Bhubaneswar with his army and dressed

as a performer at the Somavanshi court in Jajpur, he sneaked into their defenses with some of his companions. The overthrowing of the

Somavanshi rule was an internal coup, which reinstated Chodaganga as king.

Dagoba inscription says that he fought with the Pala king of Bengal, Ramapala

with the help his rival Sena chief, Vijaya Sena and defeated him at Aramayinagar.

After Vikramchoda left the Vengi territory in 1112 A.D., Chodaganga recaptured

the lost parts of his kingdom and Vengi. His later period Daksarama grant and

Mukhlingam inscription prove this along with his claims in other inscriptions

describing the vast territory of his empire.

To claim the western

borders, Chodaganga fought the Kalchuris first for the Dandabhukti (Mayurbhanj

and Singhabhum) region, where the the Kalachuri king of Tumana, Ratandeva II

was present during Chodaganga’s conquests and lost to him. A second attempt

made by Chodaganga Deva was to retrieve the lost Sambalpur-Sonepur-Raipur

tracts from the Kalachuris but he failed in doing so as proven by Kalachuri

inscriptions. He faced odds of failure in his campaign to the west.

Chodaganga Deva unified

most of the ancient Kalingan geography except the western regions and an

imperial era began. He was the undisputed ruler of a landmass stretching from the

river Ganga to Godavari after a long era of conflicts.

‘Devendravarman’ Rajaraja Deva III:

Bakhtiyar Khilji, the infamous Afghan

born Turk general of Qutb-Al-Din- Aibak occupied most of Bihar, Bengal and

parts of Assam with his overwhelming assaults. The revered ancient University

of Nalanda and its treasure trove of ancient documented knowledge disappears.

Earlier Alauddin Khilji and his general Malik Kafur had captured the Deccan

kingdoms and advanced South until Madurai moving around in a safe distance from

the Eastern Ganga frontiers for unknown reasons. Bakhtiyar sent two of his

lieutenants Muhammed-I-Sheran and Ahmed-I-Sheran to capture the Ganga domain.

The discrepancy of accounts during these events is that the Muslim chronicle

Tabaqat-I-Nasiri says that the Sheran brothers returned from their campaign

midway as Ali Mardan Khilji, a Khilji commander murdered Bakhtiyar. Many

historians including some from Odisha have unilaterally agreed that this is

true because a Muslim Chronicler who did not necessarily live during these events has

noted down so. The Daksharama temple inscription of Rajaraja Deva III openly

declares to the public that he has inflicted a crushing defeat on the Sheran

brothers while naming his general Konkana Chamunatha and mentioning a specific

hero in the battle called Kondamaa Raju.

One has to understand that such inscriptions cannot lie completely

because they are, laid in open for the common people to see in a place of

worship i.e. a Temple. This facilitates individual scrutiny by commoners. A

ruler does not inscribe false boasts openly to identify himself as a liar among

his subjects. Moreover, it was a taller boast on behalf of him to rather inscribe that the enemy got

scared and ran away from the battlefield instead of engraving that they actually

dared his might in the battlefield.

Why epigraphic chronicles can lie to a

certain extent because people who do not witness the incidents often write on

them. Their words are made available to just a certain learned section of the

ancient society and again specifically who could read them. Minhaj Juzani wrote

about this in Tabaqat-I-Nisari on a second hand basis after four decades of the

said incident. If we consider both the claims then it could also mean that the

Sheran brothers actually abandoned further continuation of ongoing hostilities

when their leader was dead elsewhere. The forces of Rajaraja I may have gained

a victory on whatever smaller contingents are, left behind while the Sherans

retreated. Because Minhaj is, also

correct about the Sherans as they actually went back and imprisoned the

murderer. Rajaraja Deva III not only protected Odisha from the invading Turks

but also prepped his successor to restructure the defenses for the upcoming

threats.

‘Rauta’ Anangabhima Deva III:

The Ananta Vasudeva temple inscription

describes Anangabhima Deva III (son of Rajaraja Deva III) as a hero born in the

lineage of Chodaganga Deva. He was extremely proud of his swift cavalry,

crossed the territories of the invading Yavanas and defeats them. Anangabhima

III was a man of foresight. Anticipating the immediate threats from the Turkic

rulers of Bengal and Delhi, he first decides to neutralize the Kalachuri threat

on his western frontiers that existed since the earlier Somavanshi rulers. With

the help of his Brhamin general Vishnu, he first retrieves the lost

Sonepur-Sambalpur-Raipur tracts after the battle of Seori Narayana on the left

bank of river Mahanadi and in today’s Raipur district. This was a long awaited

achievement for the Gangas since their rise to imperial status. However,

Anangabhima sees the usefulness of the Kalachuris as hard fighters and

establishes a marital relation with them, sealing an alliance for future

conflicts with the greater threat of Turks swarming up around his kingdom. He

accepts the Kalachuri-Haihaya prince Parmardi Deva as his son in law. Parmardi

Deva was a heroic fighter who commanded the Ganga forces in the Bengal invasion

by Narasimha Deva I later.

Anangabhima III moved his capital to

Cuttack and reconstructed the fort of Barabati on the banks of the river

Mahanadi with a capacity to host at least 10,000 archers and several other

numbers of men from different divisions of his army during any hostilities. Ghiyassudin

Iwaz Shah, the rebel governor of Bengal province who broke away from Delhi

Sultanate, invaded the Ganga territory. From the inscriptions found at

Chateswara and Anantavasudeva Temple, Anangabhima III has clearly mentioned

that his commander Vishnu defeated them in high pitched battles and the Yavanas

(Turks) were chased beyond their frontiers.

Vishnu or Vishnu Mohapatra is an unsung hero of Odia history.

Historian T.V. Mahalingam notes that

Anangabhima Deva III had raided southern India as far as Kanchi whilst an

ongoing political unrest in the Chola court. One of the Chola subjects

imprisons the Chola king Rajaraja III. The inscriptions of the Hoysala king

Vira Narasimha II corroborates the fact. It mentions that the he freed the

Chola king and uprooted a Dustha (contingent) of Tri-Kalinga forces occupying

Kanchipuram. On the other hand, the inscriptions of Anangabhima Deva III’s wife

Somala Devi is still at the Allalanatha Perumal temple of Kanchipuram dating to

his 19th regnal year. This implies that amidst continuing

hostilities with the Kakatiya king Ganapati Deva, he also raided further south.

‘Languda’ Narasinmha Deva I

(‘Yavanabaniballava’, ‘Hamiramanamardana’):

Narasinmha Deva I (son of Anangabhima

Deva III) is one of the greatest military heroes and builders of architectural

marvels of his time. His importance in the history of the subcontinent is that

he was the first successful monarch who took the war to the invading Turks

rather than playing a defensive role after the fall of Chauhans or Chahamanas of

Delhi. The primary accounts about his

achievements come from three sources – Sanskrit work of Ekavali by the Ganga

court poet Vidyadhara, the Muslim chronicle of Tabaqt-I-Nasiri by Minhaj Shiraj

Juzani who lived during his era and the Kenduli inscriptions of his descendant

Narasinmha II. His army comprised of

Ganga, Kalachuri, Haihaya, Paramara and Sena kingdom recruits, which signifies

he was leading a combined force of many ancient Indian kingdoms that struggled

to survive during the Turkish onslaughts on Northern, Central and Eastern

India.

Possibly Tughral Tughan Khan, the

Mameluk Turk governor of Khilji dynasty at Lakhnauti tried to molest the

territorial sanctity of the Gangas in 1241 A.D after which Narasinmha chose to

rather invade then wait for the next attack. Kalachuri-Haihaya prince and his

brother in law ‘Samantaraya’ Paramardi Deva commanded his forces into Bengal.

The Ananta Vasudeva temple inscription tells that Paramardi led the forces of

the war loving Narasinmha Deva I. In the year 1243 A.D. the Ganga army invaded

Bengal and laid seize on the Turk headquarter of Lakhnauti. The Turkic forces launched a counter attack.

According to modern military strategies, the Bengal invasion consisted three

tactics i.e. Deception, Bait and Bleed and Distraction in an open warfare that

includes implementation of Guerilla strategies. Seemingly as per Minhaj, the

Ganga army retreated until modern day Contai leaving trails for the Turkic army

to chase them to their chosen spot. At Contai and amidst the thick cane bushes

the Ganga forces dug in two large ditches to halt the advancing cavalry of the

enemy and left some war elephants and their fodder unattended at a place to

lure the enemy for capturing them.

As the two armies fought, the Gangas

start giving away ground to look like a retreating force. Once the slowed down

and lured in Turkic forces are on the other side of the ditches they find that

the Ganga forces have fled which actually hid in a safe distance and sent a

contingent of 200 foot soldiers, 50 horse men and 5 war elephants from behind

the thick cane bushes. The unsuspecting Turks assuming that the battle is over settle

down for a midday meal. Nevertheless, the Ganga contingent pounced upon them

from their flanks in the middle of their meals. Minhaj specifically mentions

that a great number of holy warriors or Jihadis attended martyrdom in this

sudden attack and Tughral escaped with his life from the spot to Lakhnauti

dispatching messages for help to his Turkic allies.

The following year in 1244 A.D, Ganga

forces invaded again occupying Rarh and then seizing Lakhnauti. In the first

day of seize, the Turk commander Karimudin Laghri was killed in the battle with

the contingent he led out of the gates of Lakhnauti. According to Minhaj, the

Ganga forces retreated on the second day as the message arrived about a large

Muslim army coming to reinforce the defenses at Lakhnauti from Awadh. However,

this is a self-contradicting note from Minhaj as he says that when the Awadh

governor Tamur Khan arrives with the forces, he is enraged to see the infidels

surrounding Lakhnauti and quarrels with Tughral. This clearly indicates that

the Ganga forces had not left. The further proceedings are abruptly missing

from Minhaj’s records.

Minhaj further notes that in the year

following 1247 A.D, a new Khilji governor Ikhtiyarudin Yuzbak is in place to deal with the

occupying Ganga forces. In the following years, after some initial success over

Gaur and Varendra by Ikhtiyar, Paramardi Deva defeats the Turkic forces. When Ikhtiyar

gets reinforcements from Delhi, he attacks again and in a raging battle at

Mandrana in today’s W. Bengal, Parmardi Deva is martyred. Ganga forces

continued to occupy Rarh while Gaur and Varendra passed back on to the Turks.

The primary objective of Narasinmha Deva I is completed, as the Turks never

again dare to threaten the Ganga frontiers. The Kenduli or Kendupatna inscription

of Narasinmha II speaks that the river Ganga darkened like the muddy Yamuna

because the flooding tears washed away collyrium from the eyes of several

widowed Yavanis of Rarh and Varendra after Narasinmha I’s invasion.

Narasinmha also defeated the Kakatiya

king Ganapati Deva, which is evident from his Lingaraja temple inscription and

expanded his authority beyond river Godavari. The Sanskrit poet Vidyadhara

praises Narasinmha I and II in more than hundred and fifty phrases over his

work Ekavali. He mentions Narasinmha I as Yavanbaniballava and Hammiramanamardana,

which means conqueror of Yavanas (Turks) and Muslim Amirs (governors).

Vira-Bhanu Deva II:

The Tughlaq sultan Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq

sent his son Ulugh Khan or later known as Mohammed bin Tughlaq on conquest of

Southern and Deccan India in the year 1321 A.D. Ulugh captured Telangana,

Malabar and regions until Madurai in the Tamil state. The verse no.87 of the

Kenduli copper plate grants clearly mentions that the forces of Bhanu Deva II

(great grandson of Narasingha Deva I) was actively indulged in a conflict with

the Tughlaq forces. Historian M.M.Chakravarti translates the verse as that

Bhanu Deva II’s war with Ghiyasuddin began with bloods flowing from many

warrior chiefs with their necks wounded by the valor of the king. This means

that there were causalities (of aiding insurgents) already before even the Ganga

forces battled the Tughlaqs. The verse also mentions many wounded elephants in

the battle.

From this, we can conclude that

the invasion of the Tughlaq forces on the Deccan in close proximity to the

Ganga borders actually fueled rebellious activities by some of the feudal

rulers and local chieftains. After a series of anti-insurgency activities by

the Ganga forces along with fighting with the Tughlaq forces, the only thing

gained by Ulugh was a few elephants from the Kalingan campaign. Bhanu Deva II

protected the borders of the Ganga territory after eliminating rebellions

incited by the Tughlaqi intelligence in his kingdom.

Bhanu Deva III:

During the rule of this Ganga monarch, he

confronted Firoze Shah Tughlaq, the sultan of Delhi twice at the Bengal

frontier kingdom of Panduvah. In the first attack, Firoze Shah’s Tughlaq forces

attacked a rebellious Iliyas Shah and surrounded him for 20 days at his capital. In

desperation, Iliyas asked for help from Bhanu Deva III, which does reach him. The

Dharmalingeswar temple inscription at Panchadharla in Andhra and of Choda III (a

Haihaya chieftain) describes the involvement of his grandfather Choda II in the battle with

the Tughlaqi forces at Panduvah. The inscription clearly says that

Choda II set out to provide protection to the Panduvah Sultan and vanquished the ruler of Delhi.

It also says that he presented 22 elephants to the ruler of Utkala i.e. Bhanu Deva III after

the victory. The facts can also corroborated by later proceedings as Iliyas

breaks away from the Tughlaqs and establishes his new independent Turkic rule

in Bengal by the name Iliyas Sahi dynasty and assumes the epithet Samshuddin.

However, this period witnessed Odia

forces helping a Turk for the first time and it bounced back in its after

effects. During the second invasion of Firoze Shah, the Tughlaq forces not only

defeated the Bengal Shah but also bribed some generals from the Ganga army to

switch sides for him. As a result and for the first time in history of the

Gangas whose ancient orer dependended on absolute loyalty of their subjects, a Muslim army aided by treacherous Ganga commanders invaded Odisha and a

widespread plunder and loot campaign ensued. It is said that the loot included 73

elephants mounted with treasures from the temples. In addition, an agreement

was reached according to which Odisha was forced to supply a certain amount of

elephants to the Tughlaqi forces of Delhi. The difficulties of Odisha did not

end there as Iliyas Shah himself raided the plundered Odishan kingdom

successfully from the Bengal frontier for the first time.

A new era also

started during the ill-fated rule of Bhanu Deva III as the Rajput Chauhan

branch from Garh Sambhor established its new domain in the western tracts of

Odisha with Ramai Deva as the new ruler in Patnagarh. Some historical facts say

that after the Ganga official left the Patnagarh region disintegrated and eight

local chiefs or Gauntias established their own administration as they conspired against and fought each other. Only the Chauhan Ramai Deva managed to establish order

in the region. Many other smaller

kingdoms actually came into existence during this period and the power became

decentralized weakening the absolute Ganga authority in the region. With these events unfolding, the dirty

political culture of treachery and coup attempts started in Odisha, which later

resulted in the overthrowing of the Ganga rule in Odisha by Kapilendra Deva in

the fifteenth century. Kapilendra Deva build an even greater

and new empire from the left overs of the former Imperial Ganga glory but yet

never getting rid of the politics of treachery within his ranks.

A Brief about the Ganga Military:

The Imperial Ganga army consisted of

multiple conscripts from different warrior backgrounds and kingdoms. The best

view into their military structure is from the depictions in the temples built

by them. The primary infantry soldier was a man who had his long hair tied to

the back or top of his head like a hair bun. They wore large bracelets and

anklets. Armor was seldom a part of their battle gear as the men under command

operated in harsh tropical regions and extreme topography of the battlefields.

Weight load on body directly affects maneuverability and movement. The shields

held by them are round in shape unlike the rectangular ones from the Somavanshi era. Shields

are very large to cover a leaning soldier from neck to feet while he looks out.

Shields are in use to cover the men carrying projectile weapons from the

elephant backs. Cavalry was an inseparable part of the army and as mentioned

earlier from inscriptional records, Anangabhima Deva III was very proud of his fast

moving cavalry. One structure of a warhorse from Konark temple premises that is

now a part of the Odisha government and state symbol clearly shows an unmounted rider

holding a sword and probably covering a soldier hidden behind his own shield

under the horse or possibly trampling him under his horse’s hoofs . The best

part to see here is that there is quiver of arrows hanging from the rider’s

saddle. In another, such depiction in the walls of the Konark ruins, it shows a

cavalryman shooting arrows from the back of a jumping horse. Therefore, it

clearly depicts that horse mounted archery was also a part of the Ganga army and it

was not only the Mongols who were holding such arrow shooting swift cavalries

in the thirteenth century. The Ganga

cavalry is also depicted charging while holding thrusting spears. Archery also seems to be a

very prevalent way of Ganga war making. Anangabhima Deva III also mentions in

his Chateswar temple inscription that his commander Vishnu was able to shoot

the enemies by pulling the arrow on the bowstring until his ears. A few

depictions also show archers on foot escorted by soldiers holding on to smaller

round shields.

Vidyadhara in his Ekavali mentions

Narasinmha I or II is the lord of a stream of Battalions or a huge army. From

inscriptional records, we find that the Gangas had a minister of war whose rank

is Sandhivigrahi. Military commanders have the ranks like Vahinipati,

Samantaraya and Chammunatha or Chamupati. Chamupati is specifically a leader of

a Chamu (Chaauni in Odia) or a military detachment, which has a strength of

2187 Chariots, 2187 cavalry riders, 729 war elephants and 3646 infantry

soldiers. Chodaganga in his Ronaki inscriptions mentions to have 99,000

elephants under his command, which accounts for a strength of whole army with

not less than 8, 00,000 men and 3, 00,000 animals of cavalry and elephant

corps according to ancient military way of forming battalions called Gulma. An interesting way of looking at the Ganga way of naval warfare is to

look out for Kalinga Maghaa landing on northern Sri Lanka with 24,000 soldiers.

This is a clear indication to amphibian warfare capabilities existing in

Kalinga for landing troops on distant coastal regions.

Gangas ruled over an area largely

covered with wide forests and with the best breeding grounds for thousands of

untamed elephants. Firoze Shah Tughlaq’s special interest in getting elephants

from the defeated Bhanu Deva III is an indication of how efficiently the

elephants were, trained by the mahouts of Kalinga to perform in war as a

terrifying weapon. Narasinmha Deva I is, found to be the first king of Odisha

who also bore an epithet Gajapati or the lord of war elephants. This epithet

becomes a standard for the next line of kings to rule Odisha. Even though there

were, a number of kings of smaller domains in the later phase of Odishan

history only the Kings ruling the spiritual center of Odisha could take the

title ‘Gajapati’ or the distant Ganga family members ruling in the southern

regions of Odisha could do so. However, certain south Indian kings from Kanchipuram and Vijayanagara did try to immitate this way of bearing same epithets but were never equivalent to the Odishan Gajapatis in stature or respect. The military institution of the Gangas in all is

a separate aspect of study on their existence as fine emperors, which cannot be

covered in a few words of this article.

The Srikurmam temple inscription of Bhanu Deva

II narrates that his commander Srirama Senapati was in the southern regions of his

kingdom as the Kalinga Rakhyapala.

The commander has engraved in the inscriptions for himself as the Kumelibhanjan

(Destroyer of rebellious activities) and Kondumardan (the destroyer of the

Kondus). The words like Khandapalasirachedana in the same inscription

also points to certain Chalukya and aboriginal Khandapalas who rebelled against

the Ganga authority in the region were, dealt with an iron fist. In the same

time, we find Ulugh Khan’s forces taking away some elephants from the forests

of Kalinga mentioned in the Muslim chronicles.

From this, we can conclude that

the invasion of the Tughlaq forces on the Deccan in close proximity to the

Ganga borders actually fueled rebellious activities by some of the feudal

rulers and local chieftains. After a series of anti-insurgency activities by

the Ganga forces along with fighting with the Tughlaq forces, the only thing

gained by Ulugh was a few elephants from the Kalingan campaign. Bhanu Deva II

protected the borders of the Ganga territory after eliminating rebellions

incited by the Tughlaqi intelligence in his kingdom.

During the rule of this Ganga monarch, he

confronted Firoze Shah Tughlaq, the sultan of Delhi twice at the Bengal

frontier kingdom of Panduvah. In the first attack, Firoze Shah’s Tughlaq forces

attacked a rebellious Iliyas Shah and surrounded him for 20 days at his capital. In

desperation, Iliyas asked for help from Bhanu Deva III, which does reach him. The

Dharmalingeswar temple inscription at Panchadharla in Andhra and of Choda III (a

Haihaya chieftain) describes the involvement of his grandfather Choda II in the battle with

the Tughlaqi forces at Panduvah. The inscription clearly says that

Choda II set out to provide protection to the Panduvah Sultan and vanquished the ruler of Delhi.

It also says that he presented 22 elephants to the ruler of Utkala i.e. Bhanu Deva III after

the victory. The facts can also corroborated by later proceedings as Iliyas

breaks away from the Tughlaqs and establishes his new independent Turkic rule

in Bengal by the name Iliyas Sahi dynasty and assumes the epithet Samshuddin.

Eastern Gangas in the Geopolitics of Sri Lanka:

The Imperial Gangas were directly

involved in the affairs of the Sri Lankan early medieval politics. Starting

from the indication of 'Anantavarman' Vajrahasta V marrying a Ceylonese princess

to the invasion of Kalinga Maghaa during the rule of Anangabhma Deva III, the

Gangas were deeply involved in the island’s geopolitics because of their direct

marital relations with the Sri Lankan royalties. Let me briefly note this.

The Friendly Era: Mahinda IV (945-961 A.D) who fought the Chola army of Vallabha invading Sri Lanka at Jaffna was married to the daughter of Kalinga Chakravatti that directly refers to Kamarnava I’s ruling years. Her son Sena V ascended the throne at the age of 12. Vijaya Bahu (1064-1095) married a Kalingan princess called Lilokasundari (Trilokasundari). However, the Chola king Pandu is given his sister in marriage after she begged for it despite his disagreement. He fortified Pollonnaruwa and the Chola influence decimated over Lanka. The Chola sons of Mitta are defeated by the son of Vijay Bahu called Jaya Bahu who took control of the kingdom. A native of Kalinga named as Mahinda murdered Vijaya Bahu II (1173-73). The same Mahinda VI is, murdered by Nissanka Malla of Kalingan Ishvaku dynasty in 1187 who is also known as Kalinga Lokeswara. He ruled Pollonnaruwa for ten years along with seven other members of his family to follow on. One of them was his nephew named as Chodaganga. His family ruled for the next 20 years with a gap of for 3 years in the middle. In his Dambulla rock edict, Nissanka Malla claims himself to be from Simhapur (a Ganga Domain).

The Uncordial Era: During the rule of Anangabhima Deva III, a prince by the name Kalinga Maghaa invades the Lankan nation in 1215 A.D with 24,000 conscripts from the mainland and rules the island for the next 21 years until killed in battle by the native resurgent forces of Vijayabahu III, the founder of Dambadeniya kingdom. Kalinga Magha is treated a villain in the island’s history as his period of rule was atrocious and destructive in the Island nation. He is also known as Kalinga Vijayabahu. Bhuvenaka Bahu I, the later king from 1272 – 1284 A.D is invaded by the Kalinga Rayar (Raja), Chodaganga and other Indian kings. The mention of Kalinga Rayar very well indicates either Langula Narasimha Deva I or his immediate descendants who had expansionist missions in the oceans for controlling the sea trade.

We notice from these extracts of Sri

Lankan history that the kings of Kalinga became an enemy of Sri Lankan

political order when the marital relations also ceased to exist unlike the

previous rulers.

A Resurgent Ganga who Defied the Nizamshahi, French and the British

In the mid eighteenth century, Odisha

reduced to a divided group of small principalities that were stuck in the

middle of a raging clash of interests between the Marathas, Mughals, French and

the British. The glory days of the Gangas and the Gajapatis was over as Quli

Qutb Shah gained some southern territories of the Gajapati state from the

battle-ravaged last great Gajapati of Odisha, Prataprudra Deva in the sixteenth

century. Later, the Hyderabad Nizamshahi

handed over the Northern Circars in 1753 A.D to the French. However, the Ganga

family descendants of Paralakhemundi estate were neither loyal to the Nizams

nor accepted the French authority. The

energetic ruler of the estate “Jagannath Gajapati” Narayana Deo II challenged

the outsiders. When French regents invaded his territory for occupation, he

repulsed them and understood that the ancient glory of the Ganga administration

and the disintegrating Odia land needed to unite as a combined force to reckon

with.

In 1760 A.D, he invaded the weak Bhoi

dynasty king of Khurda with the intent to control the ancient spiritual and

administrative centers of Odisha. Laying seize to the Chatragarh fort, he

defeated the Khurda forces. The Khurda king then pleaded help from the Marathas

who appeared with a much superior force at the fort in exchange of promises for

regular payments by Khurda. The French regent ruler of Vizianagaram, Sitaram

Raju at the same time invades Paralakhemundi and committed atrocities on the

commoners under the French authority. Avoiding a multi front war, Narayana Deo

II retreats from Chatragarh fort and reinforces the Jelmur (Jalamuri,

Srikakulam) fort. In the 1761 A.D, Sitaram Raju and his French high command

were defeated for the second time at Jelmur fort.

In 1766 A.D, the Nizamshahi again

handed over the same region to the British East India Company as the French

retreated due to raging conflicts with the British ships in the South. The

company authorities during their assessment of the region’s rulers also noted

down that the Zamindar of Paralakhemundi was non-cooperative in their takeover. The defiance of Narayan Deo II is, noted down

with great attention as the “Paralakhemundi Affairs” by the British officers.

On 4rth April 1768, the British and the Paralakhemundi forces clashed at Jelmur.

The British had the support of the Nizamshahi authorities while the local

rulers of Athagarh and Khalikote helped Narayan Deo II. Due to superior weapons and better supplies

of the British, the Parala forces endured defeat and Narayan Deo II fled to

live and fight another day. As the British established their own regents in the

estate and left, Narayan Deo II reappeared and took over the administration

from the British regent with the help of his loyal subjects. Until his natural

death in 1771 A.D, Narayana Deo II remained defiant to any foreign authority

over his people. The British could never deal with him. His was the first armed rebellion against any European power in Odisha and possibly in whole of undivided India.

Ending Notes:

Serious discussion and research on

several aspects about the Imperial Gangas besides their military history is a

need of the hour. There are few misconceptions in the first place that need to

go. Some questions are about their origins. Are they an offshoot of the Mysore

Gangavadi? Were they Telugu or Dravidian? The new research throws light on the

origins of Eastern Gangas as even older than the Mysore branch. Rajaraja Deva

I’s inscription specifically mentions his war with the Drabila or Dramila

(Dravida) which signifies that Eastern Gangas identified themselves as

Non-Dravidian. Dr. Harihar Kanungo in his books and articles has proved that

they existed even during the Mahabharata era and has linked them to many

ancient races like the Drahyus and Mahisyas. He also points out that there

existed five Ganga princedoms inside the territory of W. Bengal, which are older

than that of the Mysore Gangavadi branch. The Odia Saptasati Chandi Purana

describes a king founding a new kingdom between Agrabada to Gangabada. This

Gangabadi is today a village situated sixteen miles from the Naupada station in

Andhra side of the border with Odisha and renamed as Gangabala by the railway

authorities. The Kendupatna grant of Narasimha II also mentions this Gangabadi

clearly. However, Gangabadi also means the region under the Ganga family’s

control.

Third century B.C.E Greek naturalist

Pliny writes about the Gangadhikar or Gangahirdae Kalinga along with two other

Kalingas in his Natural history. There still exist a community in Mysore known

as Gangadikar Vokalingars who, claim descent from the Talakad Gangas of

Karnataka.

The conflict with the mention by

Chodaganga Deva as descended from the Mysore Gangavadi prince Kamarnava over an

inscription is that there is a gap of at least seven hundred years between both

of them. Moreover, his grandfather Vajrahasta V and father Rajaraja I claim their

descent from Tri Kalinga without any such farfetched connections of ancestry in

their inscriptions. Chodaganga Deva claiming his long stretch of ancestry linking up to puranic charachters at a

point when he desperately needed widespread recognition by the people is not a

new thing in the political history of India.

Several inscriptions found inside

present Andhra territory are mostly in Sanskrit with influence of both Odia and

Telugu words along with scripts of Odia and Telugu separately from Devanagari.

It would be bigotry to link the origin of the Gangas to any linguistic

community. Yes, the Gangas did achieve the pinnacle of their greatness as Odia

kings later despite their wider origins that trails back to every corner of the

Indian subcontinent and broad scale enthusiastic research is required for

finding more.

Note "Ownership of any photographic illustrations or the screenshots is not claimed by the author"

Some References for this Article

- The Orissa Historical Research Journal, Volume IV

- The Orissa Historical Research Journal, Volume V

- Inscriptions of Orissa, Volume III (Part I)

- Inscriptions of Orissa, Volume III (Part II)

- Andhra Historical Research Society, Rajahmundry, Volume I (Part II)

- History of Orissa by R.D.Banerji, Volume I

- Anchalika Janasruti O Ithihasa by Kailash Chandra Dash

- Orissa Under Anangabhima Deva III and Narasimhadeva I (Paper on http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in)

- Ekavali Vidyadhara Tarala Of Mallinatha Kamalashankar Pranshankar Trivedi

- Kalinga Under the Eastern Gangas: Ca. 900 A.D. to Ca. 1200 A.D. by N. Mukunda Rao

- Itihasa, Paramapara O Shri Jagannath by Harihar Kanungo

- Outlines of Ceylon History by Donald Obeyesekere

Research Document Submitted by Manjit Keshari Nayak

(About author - Volunteer self research analyst and writer on the History of Odisha)

(About author - Volunteer self research analyst and writer on the History of Odisha)

Like our Page at www.facebook.com/PurnyabhumiOdisha

Email- punyabhumiodisha@gmail.com

Email- punyabhumiodisha@gmail.com

Excellent piece....

ReplyDeleteOne of the finest articles on collated details about the Gangas of Odisha

ReplyDeleteExcellent presentation

ReplyDeleteVery nice .. !!

ReplyDeleteodisha is land of warrior's

ReplyDeleteExcellent.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteNamaskar, Shrijukta Manjit! Very interesting observations and a trove of fact based info compiled and curated by you! Kudos to you!! I have always been fascinated by our heritage and glorious past ; plus, the presence of such clues in written works, day to practices, language, similarities between disparate groups of people in different places etc.

ReplyDeleteWould it be possible for you to share the secondary & primary sources of your facts and discussion? I would love to read more in-depth info on the same.